Medersa Bou Inania

If there is just one building you should seek out in Fez – or, not to put too fine a point on it, in Morocco – the Medersa Bou Inania should be it. The most elaborate, extravagant and beautiful of all Merenid monuments, immaculate after renovation, it comes close to perfection in every aspect of its construction: its dark cedar is fabulously carved, the zellij tilework classic, the stucco a revelation. In addition, the medersa is the city’s only building still in religious use that non-Muslims are permitted to enter.

Set somewhat apart from the other medersas of Fez, the Bou Inania was the last and grandest built by a Merenid sultan. It shares its name with the one in Meknes, which was completed (though not initiated) by the same patron, Sultan Abou Inan (1351–58), but the Fez version is infinitely more splendid. Its cost alone was legendary – Abou Inan is said to have thrown the accounts into the river on its completion because “a thing of beauty is beyond reckoning”.

At first, Abou Inan doesn’t seem the kind of sultan to have wanted a medersa – his mania for building aside, he was more noted for having 325 sons in ten years, deposing his father and committing unusually atrocious murders. The Ulema, the religious leaders of the Kairaouine Mosque, certainly thought him an unlikely candidate and advised him to build his medersa on the city’s rubbish dump, on the basis that piety and good works can cure anything. Whether it was this or merely the desire for a lasting monument that inspired him, he set up the medersa as a rival to the Kairaouine itself and for a while it was the most important religious building in the city. A long campaign to have the announcement of the time of prayer transferred here failed in the face of the Kairaouine’s powerful opposition, but the medersa was granted the status of a Grand Mosque – unique in Morocco – and retains the right to say the Friday khotbeh prayer.

The interior

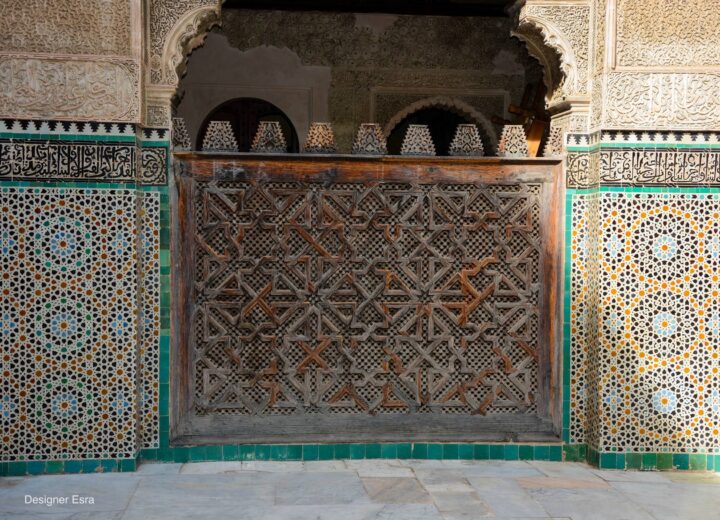

The basic layout of the Medersa is quite simple – a single large courtyard flanked by two sizeable halls (iwan) and opening onto an oratory – and is essentially the same design as that of the wealthier Fassi mansions. For its effect it relies on the mass of decoration and the light and space held within. You enter the exquisite marble courtyard, the medersa’s outstanding feature, through a stalactite-domed entrance chamber, a characteristic adapted from Andalusian architecture. From here, you can gaze across to the prayer hall (off-limits to non-believers), which is divided from the main body of the medersa by a small canal. Off to each side of the courtyard are stairs to the upper storey (closed to the public), which is lined by student cells.

In the courtyard, the decoration – startlingly well preserved – covers every possible surface. Perhaps most striking in terms of craftsmanship are the woodcarving and joinery, an unrivalled example of the Moorish art of laceria, “the carpentry of knots”. Cedar beams ring three sides of the courtyard and a sash of elegant black Kufic script wraps around four sides, dividing the zellij from the stucco, thus adding a further dimension; unusually, it is largely a list of the properties whose incomes were given as an endowment, rather than the standard Koranic inscriptions. Abou Inan is bountifully praised amid the inscriptions and is credited with the title caliph on the foundation stone, a vainglorious claim to leadership of the Islamic world pursued by none of his successors.

The function of Medersas

Medersas – student colleges and residence halls – were by no means unique to Fez. Indeed, they originated in Khorasan in northeastern Iran and gradually spread west through Baghdad and Cairo, where the Medersa al Azhar was founded in 972 AD and became the most important teaching institution in the Muslim world. They seem to have reached Morocco under the Almohads, although the earliest ones still surviving in Fez are Merenid, dating from the late thirteenth century.

The word medersa means “place of study”, and there may have been lectures delivered in some of the prayer halls. However, most medersas served as little more than dormitories, providing room and board to poor (male) students from the countryside, so that they could attend lessons at the mosques. In Fez, where students might attend the Kairaouine University for ten years or more, rooms were always in great demand and “key money” was often paid by the new occupant. Although medersas had largely disappeared from most of the Islamic world by the late Middle Ages, the majority of those in Fez remained in use right up into the 1950s. Non-Muslims were not allowed into the medersas until the French undertook their repair at the beginning of the Protectorate, and were banned again (this time by the colonial authorities) when the Kairaouine students became active in the struggle for independence.

Since then, restoration work, partly funded by UNESCO, has made medersas more accessible, although it will still be some while before all the work is complete – at the time of writing, for example, the Medersa es Seffarine and the Medersa es Sahrija were both closed for renovation. As restoration across the city continues, accessibility is impossible to predict.